When I was twelve, a buddy of mine invited me and a few others over to his farm for a sleepover. The activities will be familiar to people in the remote country, comprising driving go-carts, running around in the woods, and a tractor joy-ride in the middle of the night to harass the girls sleeping over a couple miles away. Gazing over the starry landscape of the countryside at 1:00 A.M. as the heavy groan of the tractor as it made its way through the dirt roads remains one of my most cherished memories.

The next morning, his dad pretended he wasn’t aware of the shenanigans the previous night, but he had a job for us. Outside in a cage were two dozen chickens. They were meat chickens, and today was the day to slaughter them. I never found out whether this was his way of punishing us, or he simply wanted the work done and saw free labor. In any case, the dad took the six of us, gave us all a knife, and told us to cut off the chicken’s heads. One watched in horror, a couple in nervous trepidation, and the rest in delight. I was in the middle group, and I observed the enthusiastic ones do the first killings. As required, as they chopped off their heads, they let the chickens go, their headless bodies flapping around before collapsing to the ground, giving a slight twitch before ceasing movement altogether. I remember taking the knife and feeling the blade cut through bone, severing it, then watching the life go out of its eyes as I placed its head in the pile. Afterwards, we were tasked with de-feathering the animals, and then the farmer gutted them.

Time has changed my location and the general culture. My childhood vista of sprawling, flat countryside turned into swaths of houses when I moved. I went from living in a village surrounded by corn fields to mass suburbia next to a large city. As much as I liked to make fun of the clueless city dweller, I wasn’t any better. In that span, my main social groups transformed from rural blue-collar types to suburban white-collar professionals. I developed far more professional and urban cultural contacts through traditional communities, all of which I am grateful for, but my new life came at the expense of losing my connection to the land and the people caretaking it.

This became clear when I was informed by a family friend of a co-op in the area, where she had bought meat for over a decade. She was a huge fan of raw milk, and the only way to get it in this state is to “buy” part of the cow, which will give you rights to everything coming from said cow. She was also a big nutrition fanatic and talked about the virtues of grass-fed beef long before it was cool and took part when the co-ops were in a major legal gray area, populated by hippies and crunchy types. Now farmer’s markets are inundated with our types to the extent many try to kick our type of people out of them. Sourcing good meat has become essential for anyone, left or right, who respects their food.

Deciding it would be an excellent opportunity to get some better-quality food than the store stuff, and with a penchant for trying something different, my wife and I joined it. We bought our quarter cow from the local co-op, the farmer being a friend of a friend who kept his grass-fed livestock on a pasture an hour away from us.

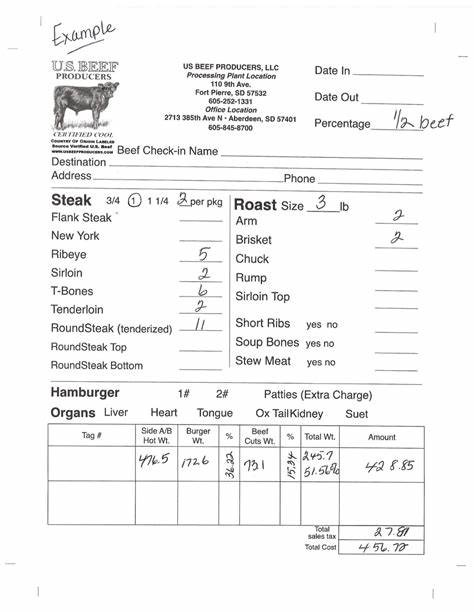

When the cow was ready, we got a call from the butcher asking me to fill in a cut sheet. It was a simple piece of paper where we were assigned to put checkboxes towards the priority in cuts that we wanted. No web forms, no explanation, just plain text. In the age where everything is done through fancy online pages that eat up hundreds of megs of memory, the simpler things are underserved. I went over the cut sheet, realizing that while I could navigate most of the cuts, I needed to dramatically increase my skill set in preparing them properly and, most importantly, go outside my comfort zone and deal with completely foreign parts to make use of.

Do I want brisket? I’d only done it once, but now it seemed to demand my attention. I had beef liver twice, though I’d known it to be a superfood for my entire life. How do you create tallow from beef fat? Then there was the price. Where I usually went to the store and stocked up on ground beef when it was on sale, and occasionally a steak when it was REALLY on sale, the idea of spending almost six dollars per pound struck me as onerous to our food budget. I realize today that price is a steal in much of the country. I had to make it last.

The window to pickup was limited to a two-hour span on a Friday morning. I had to take some time off work to drive there. I pulled into an area of the city where I had to keep my eyes peeled to avoid getting mugged. Inside a dilapidated, rusted building was piles upon piles of frozen meat, with customers walking in with massive coolers to transport their freshly butchered beef. Also, in a fridge in the corner was multiple gallons of raw milk. I didn’t take the plunge to buying it on this occasion, but I know that now I’m in this culture, it was inevitable I would eventually. There were three young Mennonites and a middle-aged woman manning the operation, relying on a clipboard to a thirty-year-old electric calculator to ring everyone up. I checked the packages, all professionally wrapped and fresh. I noticed the two-pound package of pure fat, which I would learn to produce tallow with. There was cow tongue, which I would try and fail to cook into something edible. Then there were the steaks, a few of which I selected to celebrate my birthday in a few weeks. I wrote my check for a little over a thousand dollars and piled the meat in my coolers for the drive back.

There is an endearing quality in the low-tech, un-optimized atmosphere of co-ops. They don’t have savvy web designers, financial analysts, and the limitation in scaling is more a feature than a bug. They are workmen with a particular skill set, whether it be raising cattle, butchering the meat, or organizing some trusted colleagues to handle simple logistics, that creates intimacy in what in modern times is often a sterile transaction. Instead of paying for your beef in an automated checkout after taking it from the aisles of a mega-chain, put there by an unknown employee, raised by an unknown farmer, and transported by an unknown semi driver, you know the people involved with every part of the transfer from the farm to your freezer.

I could go to my neighborhood Kroger, buy a sirloin steak, and drive it back to the house to grill within fifteen minutes. With the co-op, we have to first contact the farmer about when a cow will be ready, talk to the butcher about cuts, then find the logistics of picking up the meat. All of these tasks take hours of time and require weeks of planning. While the shipment will last for several months, there is still more hassle involved. When we progressed to a more technological society, those hassles disappeared, but so did the relationships those hassles helped promulgate. Friendships that were based on trusted transactions and a firm handshake passed away, and losing such bonds made us more atomized and alone.

At the micro level, one will not see much of a societal difference to an individual taking this route. The local grocery store sees a slight loss in business and the local farmer gets paid a little better. However, with all the parts of a network being associated with specific people doing specific tasks, the technological abstractions that govern our society fall away. I never felt loyalty to my local Kroger, though I never had a problem with their service. I do, however, feel loyalty to the butcher, the co-op, and my friend who introduced our family to it. What was once a mechanical, transactional relationship with a faceless entity becomes a relationship with a flesh-and-blood human being, with all the foibles and strengths accompanied with those interactions.

One of the shocking aspects of sales coming from an engineering background is the amount of sway purely human factors have over purely technical elements. We’ve regularly sold software that was priced higher and had fewer features than our competitor because the buyer was a friend of someone high-up in our organization, and he knew that we would have his back if he got in a pickle because of the long-existing relationship. We would too, because contrary to common belief, friendships are important, and often there’s negligible difference between a friendship based on business or something like a shared hobby. It's a strange aspect of modern society that people denigrate these business relationships as being insincere.

While we didn't go out for beers with the butcher who took our order over the phone, or bowl with the local farmer, we did converse with them. From the perspective of pure humanity, such trivial conversations are the lifeblood of a community. These interactions compound as more and more lives get involved, and soon you find yourself with a network of like-minded people who, often without consciously realizing it, escape the system. Their mindset changes, their loyalties update, and suddenly you have a minor clan organically developing, comprising millions of small alliances and unspoken expectations.

A positive aspect of the new political realignment is that we can reassess what it means to have certain viewpoints, especially those which were once the domain of the other side. It also means there is far less need to take a binary stance just because your enemy takes a side. It’s a well-known and tragic fact that our meat sourcing is outright barbaric. Most every industrial facility pack animals into horrifically cramped cages, and often these creatures go through their entire lives never seeing the sun. PETA is correct in showing the immorality of these even if their solution of veganism is incorrect.

As we become separated from the land, so do our instincts for proper ecology. Anyone who walks into an industrial pig farm knows something is immoral with these practices and it churns any sensible man’s stomach. Even though we are raising these animals solely for their meat, putting them in these facilities is a crime against nature. There is supposed to be a mutual respect between man and his food, and mass processing compounds sever it. This is our prime opportunity to create a different mindset, one that can resonate across the political spectrum. We are far past the politics of defending massive corporations and calling co-ops and such hippie communist nonsense. Now’s the time to re-align.

One could argue that while co-ops, pasture-fed livestock, and the like is nice, it could not produce enough meat and would make it more expensive for many. And they’re correct. My family eats about 30% less meat than before, and we almost always mix it into a stew, put it into a rice dish, and use other means to add calories. The bonus is that the meat we consume is far superior, with even ground beef having a far better flavor and texture on top of having superior nutrition. The time and resources a family has to take up more work and money for a necessity like food varies greatly, but I know a family of seven who takes SNAP benefits that manage to fit local meat into their budget. Paradoxically, the increase in prices may be a prime opportunity to push these alternatives. If you’re going to pay an arm and a leg for food, it might as well be high quality.

To take the philosophy a step forward, the rise of work-from-home and the increasing instability of cities has created a new movement to immigrate to rural areas and homestead. I have nothing but respect for the people who do this, and visionaries like

, , Catholic Land Movement, and countless others are leading the way. For many, the idea is to do professional jobs remotely while also planting crops, raising animals, and building rapport with like-minded people to unique, resilient communities outside the purview of major power centers. While laudable and a positive step to make, this option isn't available to everyone through no fault of their own, especially those whose profession requires close access to cities and suburban centers of power for clients.There are also logistical reasons, as even if everyone could live in that way, it would not be ideal. Productive societies have a division of labor for a reason, and insisting every family be their own farmer, butcher, and defense will create more resilience if the basics become rare in collapse, but also induce a culture too burdened with supplying necessities for survival that they have no ability to impact on the larger world. We are far off-balance in the urban-rural divide, but the extreme of telling everyone to buy land and farm isn’t balanced either.

Living in modern society requires tradeoffs, and it's just as important to impart our own networks and culture in large cities as it is to make resilient infrastructure through relationships and transactions with people of the land. Not every person needs to be their own farmer but being able to handle a garden and having friends you can buy fresh crops from is a huge plus. You don't have to be your own butcher, but having a personal butcher and having a passing knowledge enough to talk shop is a vast improvement from the status quo. There is a mutual benefit to these as well, as people residing in cities have access to financial and cultural networks that will be completely opaque to those living in rural areas.

Trump is famous for his ability to walk into your average store and restaurant and joke and laugh with the employees within a minute. The man who spends most of his time meeting with high-powered executives and politicians has an instinct for how even the typical young employee ticked. He’s able to do this because he has an innate respect that can’t be faked along with esteem for people who do productive work, regardless of their station in life. No other politician has come close to his skills, and whenever someone tries to mimic his abilities, they always embarrass themselves with the most robotic and uncomfortable dialogue you can imagine. Men die for a leader like that.

Imagine what we could do if the average city dweller had such a holistic view of society. Imagine If, instead of your local farmer being treated like a cog by faceless multinational conglomerates, he was able to see the name and faces of the people he worked for. Imagine in a small town ravaged by opioids, a local guy from the city would drive over for his beef, and during the pickup he was told of a great business idea from a local entrepreneur. Imagine if that urban guy with personal contacts took the budding businessman under his wing into the insular world of venture capital.

The core weakness of the managerial class presiding over us is their dismissal of Nature for abstractions. It's why the hick-lib has to constantly spout his contempt for his village hometown in order to make room for his ideological programming. They are good at managing, good at abstract signaling, and good at the technical aspects of their niche industry. They seek to use people of the land, abstract them into widgets, and wipe away their humanity.

However, in their obsession with process, scaling, and financial tricks, they've caged themselves into a rigid and mechanical thought process. For all their talk of diversity of thought and open-mindedness, they would be the first to blanch at how a farmer talks in the fields or a mechanic in the shop. The class divide has never been starker, and many upper-class people rarely, if ever, interact with middle and working-class citizens, relying on the stereotypes of the urban monoculture to fill in how they tick. They have a massive blind spot for how middle and working-class populations operate, and the importance of the tribal knowledge they’ve earned through years of performing their craft.

The book The Idea Factory goes into length on how our country found the elites of society from your most average looking towns, and they transformed the world. We used to bend over backwards searching for talent in the most remote places, and many of them became some of the greatest innovators our times have ever seen. Instead of nurturing the rough intellectual capital in our own nation, we now import them.

Rural areas are ravaged with drugs while our managerial class shrugs or laughs. City dwellers are stuck in a hopeless grind and every transaction goes through an impersonal store where every employee churns out to other work within six months. No one is getting the better part of this fruitless divide. Rural areas are far from wholesome-chungus, and are increasingly plagued with the same issues of modernity as the most shitlib of cities. The dysfunction of suburbs and cities are well known, and the insularity and atomization of society continues unabated.

What we need, more than ever, is to bridge this divide, both in the rural and urban worlds as well as working and white-collar-professional classes. It starts with making connections, making relationships, and putting our money on the table to move forward. Not too long ago this symbiosis of different people was taken for granted, and we can regain it.

Thank you for reading this edition of Social Matter. If you liked this and have not subscribed, please consider doing so. For subscribers, please consider sharing this article. Your support means the world to me.

-Alan

I've not seen it said better, Alan. Thank you. We've lost connection to each other, which being a sometime cynic, might have been planned. Regardless of the cause, isolation at every level of the society, and within groups and sub-groups, seems to have become the norm, the dividing lines seem to have hardened. To reverse that trend we will have to give up something; convenience, time, a bit more money, etc.; but to get something of far greater value in return. Thank you too, for the kind words.

Look i have some issues with this but i suck ass at long posts so i’m going to boil it down.

How big does a city actually need to be to work as you describe? When does the trade off of size and “efficiency” for everything else stop being worth it? How do you ensure the cities don’t just revert to intelligence and morality shredders? Could “large towns” do a “good enough” job at being cities without as many of the massive downsides?

I don’t think your post satisfyingly answers the above questions. I realize this topic is a very complex and nuanced one but nobody has time for that. From my perspective, big cities cons outweigh the pros.

Completely separate topic, but I wonder how much of the “efficiency gains over time” graph people like wheeling out when complaining about the 40 hour workweek and lack of pay increases is due to the gutting of social relationships to streamline everything. If so my abject hatred of globalism and internationalism only deepens.